alden wrote:The influence of Ian Fleming and Noel Coward is present in you book. Can you tell us about these two men and how they influenced dress?

Noel Coward was very much the dandy and the picture of him standing in the Nevada desert in a brown DJ (pg.93) has some Salvador Dali (whose tailor was Rovito in Paris) about it.

BTW, I thought you might like this picture of another dandy and A&S client, Rudolf Valentino.

Michael

Valentino, Coward, Fleming and Buchanan

Rudolph Valentino

With pleasure and I hope that you do not mind if I add something about Valentino and Jack Buchanan too. We all now remember Cary Grant but we should not forget the influence of men such as Rudolph Valentino who enjoyed a popularity and a status which did even rise above the fame of such as CG - indeed CG refused to ´play´ Rudolph Valentino, who was still being referred to as a ´big shot´ decades after his death, in ´Sunset Boulevard´ which, strangely, had the same cinematographer as Four Horsemen - John Seitz . Here is a short piece about Valentino, originally in my book:

Rudolph Valentino (born Rodolpho Alphonso Rafaello Piero Filiberto Guglielmi 1895-1926) was one of the first great stars of the (silent) screen; starring in films such as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (in which he spectacularly introduced the Argentinian tango to a wider audience with Beatrice Dominguez - who died before the film was realeased), The Sheikh and Son of the Sheik. Although they are over-acted in a wide-eyed, over-demonstrative way and even though the footage is black and white and old and crackling, it is still possible to see the star that briefly shone. Rather like Cary Grant, even now, most people have heard of Rudolph Valentino and even recognize him. The feverish, on-screen adulation which he inspired was not reflected in his personal life. Twice married and twice divorced, he did not seem to find and keep any woman; indeed, he said: ‘Women are not in love with me; I am just the canvass upon which they paint their dreams.’ When he died, at 31, of peritonitis, following an operation for a gastric ulcer, the public mourning was great and the streets of New York were lined with hundreds of thousands of weeping mourners - and Pola Negri threw a fit at the funeral - for which she was heavily criticised at the time, as her sincerity was doubted - but 10 years after his death she still mourned him. The anniversary of his death is still marked at the mausoleum where he was entombed in a vault originally reserved for the husband of his friend June Mathis. The vault was, at first, ‘borrowed’ and later quietly bought by his estate. Legend has it that he was buried still wearing the platinum slave bracelet and watch given to him by his second wife, set designer Natacha Rambova. For many years, following his death, a mysterious ‘lady in black’ used to appear at this annual ceremony. He was not, in fact, originally, the poor Italian boy of popular fancy but the son of a veterinary surgeon. Owing to his French mother, he spoke French as well as Italian and also learned English and Spanish and had some knowledge of German. The catalogue of the sale of his effects, following his death, shows that he had an extensive library and many valuable, even museum quality, antiques - especially furniture, doors, paintings, arms and armour (which he brought from his European tours), as well as the latest motor cars and four Arabian horses. Everything was sold off for a song to pay debts, following his death. His life was a far cry from following the cult of ignorance which governs the tastes and values of most modern celebrities. His former house (in a Spanish style) Falcon Lair, above Beverly Hills, has recently been stripped of most of the cladding materials and the site will probably become a ‘condo’ - in the best modern taste. He was not an innovator in dress but a great admirer and follower - indeed exponent - of timeless British style.

Noel Coward

Sir Noel (Peirce) Coward 1899-1973 - playwright, diarist, actor, songwriter, cabaret artist, film director and producer, leader of fashion; a polymath known as ‘The Master’: ‘But I believe that since the day my life began, the most I’ve had is just a talent to amuse’. From youth he frequently teamed up with actress-singer Gertrude Lawrence (1898-1952), born as Gertrude Alexandria Dagmar Lawrence-Klassen. He wrote several plays for her. George and Ira Gerschwin wrote the song Someone to Watch Over Me for her. She got Rodgers and Hammerstein to write The King and I and her stage performance in this was her most successful role. Coward sent her a couple of superb telegrammes. On one of her opening nights in a play he sent the words: ‘A warm hand on your opening’ and when she got married, he wrote:

‘Dear Mrs A, Hooray, Hooray,

At last you are deflowered,

On this, as every other, day,

I love you –

Noel Coward.

He lived in Jamaica (in a house called Firefly, near friend Ian Fleming’s Goldeneye) and in Switzerland. Plays, Revues and musicals include: The Vortex, Private Lives, Tonight at 8.30, Cavalcade, Design For Living,, Charlot Revues, Bitter Sweet, Blithe Spirit, Present Laughter, Nude With Violin, Operette, This Year of Grace. In 2006 Hay Fever was back on the stage in London with Dame Judi Dench. Some famous songs include: I’ll See You Again, If Love Were All, Don’t Put Your Daughter On the Stage Mrs Worthington, Uncle Harry, Mad Dogs and Englishman, Mrs Wentworth-Brewster, Poor Little Rich Girl, Mad About The Boy, Don’t Let’s Be Beastly To The Germans. Films produced by him, include: the great classic Brief Encounter, This Happy Breed (starring Robert Newton, 1905-1956, a fine actor, now chiefly remembered for the overblown (but lovable) characterization of Long John Silver in the 1950 Disney film of Treasure Island). There is also the wartime propaganda film In Which We Serve (which brought the King and Queen to the film set). He appeared in Our Man in Havana and The Italian Job as well as In Paris When it Sizzles and Boom. When James Bond creator Ian Fleming asked him to play Dr No in the first Eon Productions’ Bond film of the same name, Coward, fed up with witnessing the Flemings’ marital bickering, replied: ‘The answer is: No…No, No, No, No.’ On one of his visits to America Coward was tracked down by a newspaper reporter, as he was about to board a train. The puffed-out reporter blurted out:”Mr Coward, Mr Coward, do you have anything to say to the ‘Star?’’ Coward turned and said: “Yes - Twinkle.” He had spent happy childhood holidays in Charlestown in Cornwall and when the new steeple of the Church was erected and bells installed, he paid for one - called Noel - which was tolled out to sea when he died. A great style icon of the 1920s and 1930s, he popularized the polo neck jumper, the dressing gown on stage and favoured quite modern tailors such as Michael Fish in Clifford Street and Douglas Hayward in Mount Street. Archie Leach said that he drew mainly on Noel Coward, Jack Buchanan and Rex Harrison when he created Cary Grant - ´I became someone I wanted to be - or he became me...´

Ian Lancaster Fleming (1908-1964)

A member of the family which owned Fleming´s Bank, his early life was overshadowed by his father´s life and heroic death in WWI and also by the success of his elder brother Peter (author of such amusing works as A Brazilian Adventure. He took some time to develop and, after intelligence work in the RNVR (the wavy navy) in the war, he became a journalist on the Times writing the Atticus column, before buying land in Jamaica on which to build a getaway from the English winters and where he wrote the Bond books. He is more of a purely personal choice for me as I read the Bond books when still quite young and there is so much more in them than in the films especially about dress - although the early films are, to me much, much better than the later offerings and the influence of Terence Young shines through them. Young coached Connery for the role; even to the extent of introducing Connery to his tailors and his shirtmaker, Turnbull & Asser, who had just designed their cocktail cuff and it was chosen as a signature garment for Bond. Terence Young directed Dr No, From Russia With Love and Thunderball and is acknowledged as the inspiration for the screen persona and appearance of the James Bond of these early films – less sinister (and much more humorous) than the character in the books. Sean Connery is, certainly, and by a vast majority of those over 35, regarded as the definitive screen James Bond. Even Ian Fleming warmed to his performance, after initial doubts - and even introduced some Scottish ancestry for Bond in later books. Sean Connery appeared as Bond in seven of the films: Dr No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever, Never Say Never Again. Probably the best for me is From Russia With Love; although Goldfinger was one of the first films that I ever saw on the big screen (remember when Bond lies with his tender parts threatened by a laser and he says to Goldfinger (played by Gert Frobe): ‘Do you expect me to talk, Goldfinger?’ Reply: ‘No, Mr Bond, I expect you to die!’). It was certainly the film that helped me to prevail in my rebellion against having to wear short trousers: because James Bond did not wear them! Charles Gray’s impersonation of Ernst Stavro Blofeld in Diamonds Are Forever has given us one of cinema’s great villains (Charles Gray: born Donald Marshall Gray 1928-2000). According to Andrew Lycett’s biography of Ian Fleming, the author was trying to name the villain in his latest book when he came across the name of fellow Old Etonian Blofeld amongst the members of Fleming’s club and just added Ernst Stavro to it, giving him an East European identity. According to the novels, Blofeld shared Fleming’s own birthday (28th May1908). The real Blofeld who gave his name to this villain was a member of an old Norfolk family and the father of cricket commentator Henry Blofeld (born 1939) who was known as ‘Blowers’ to fellow commentator Brian Johnson (1912-1994) – ‘Johnners’; well known for his co-respondent shoes and his on-air consumption of cake at teatime. I think that it is Fleming´s poise and assurance that appealed to me as a little boy. Fleming´s friend Roald Dahl used to say that Fleming coming into a room brought in a big red glow.

Jack Buchanan

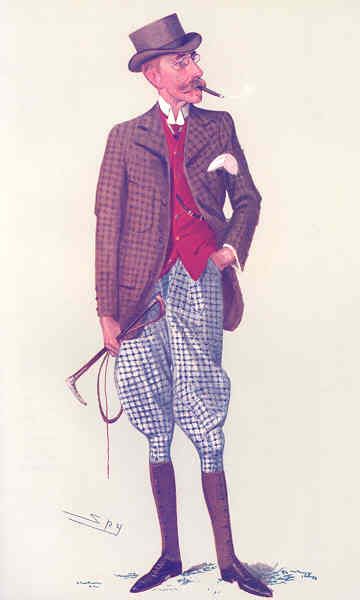

Jack Buchanan, 1891-1957, British actor, singer and impresario (star of stage and screen on both sides of the Atlantic) and, after a shaky start in the music halls of Glasgow (having, not pennies but sharpened rivets thrown at him as a signal to 'get off'), he starred in Andre Charlot's Revues and then teamed up very successfully for many years on stage, screen and in real life with singer-comedienne Elsie Randolph. He financed fellow Scot, John Logie Baird, in his pioneering work on the development of television at his workshop in Vicarage Lane, Ilford, Essex and, later, at Crystal Palace. There are sound recordings of him singing numbers such as Fancy Our Meeting, Goodnight Vienna and Her Mother Came Too as well as a number of amusing knock-about comedy films, largely co-starring Elsie Randolph - as well as The Band Wagon in which Fred Astaire (very much in the spirit of the film, as a matter of fact), graciously goes into a low gear to allow the ageing Buchanan one of his last memorable screen moments, in the number 'I guess I'll Have to Change My Plan' - that they sing and dance together. Modest and self-deprecating, it was said of JB 'No one ever threw any mud at Jack Buchanan - because there was no mud to throw. JB built and lived on top of a theatre which became the Odeon West End (about to be demolished, to benefit property developers who are going to erect a monstrous hotel on the site, on the south side of Leicester Square). JB also later managed the Garrick Theatre and lived in Mount Street, Mayfair where there is a privately erected blue plaque to his memory - as English Heritage (inexplicably) refused to erect an ‘official’ plaque to him. He is sometimes credited with the introduction of the double-breasted dinner jacket, made by either Frederick Scholte or Hawes & Curtis (a design taken up by the Duke) and, as mentioned in connection with Noel Coward, was one of the stars on whom Archie Leach said that he based Cary Grant. According to Michael Marshall's biography 'Top Hat and Tails - The Life of Jack Buchanan' - on being carried out, on a stretcher, from his flat in Mount Street, to go to the hospital where he would die, he called for his pearl grey Herbert Johnson trilby hat to be placed on the stretcher...and the foyer cleaners at the Garrick Theatre (where he had been performing, up to the last), until they retired, every day put a vase of his favourite clove carnations under Baron's magnificent photograph of him, which used to hang in the foyer and is now, sadly, out of general sight, in the royal retiring room.

NJS