The Frock Overcoat

Posted: Wed Sep 24, 2008 6:28 am

The Frock Overcoat or Albert Top Frock

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the frock coat established itself as the correct form of daywear full dress coat, displacing the dress coat to the status of evening wear.

It should also be made explicit that the word ‘coat’ does not traditionally denote outwear or an overcoat for outdoor wear. Tails coats such as the morning coat (day wear tail coat) and the dress coat (evening wear tail coat) are both coats, but are not outerwear. Coats can therefore be distinguished as either overcoats or ‘undercoats’ – although the latter archaic expression was used only in the early 19th century. The frock coat is an ‘undercoat’, and the top frock is an overcoat.

It is interesting that the frock coat may have evolved from a type of overcoat. Between 1820's to 1840's, a particular subtype of frock coat existed called the surtout that was half under-coat and half over-coat (Cunnington & Cunnington, The Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century). Here is an example from an original 1854 Parisian fashion plate I have in my possession:

Notice that the wearer is wearing only a waistcoat underneath the coat, thus making it an undercoat, which is nonetheless three quarter length in a manner more typical of overcoat. It has features that are half undercoat and half overcoat.

As the frock coat became established as the Prince Albert for wear with daytime full dress, an overcoat known as either a “top frock”, or the “frock overcoat” emerged, cut to be worn over the frock coat. Cutting manuals state that a little measure should be added to the proportions of the client’s frock coat to make this overcoat.

It cannot be emphasised strongly enough that the frock coat is not an overcoat or outerwear. When outerwear was worn, the frock overcoat served this role:

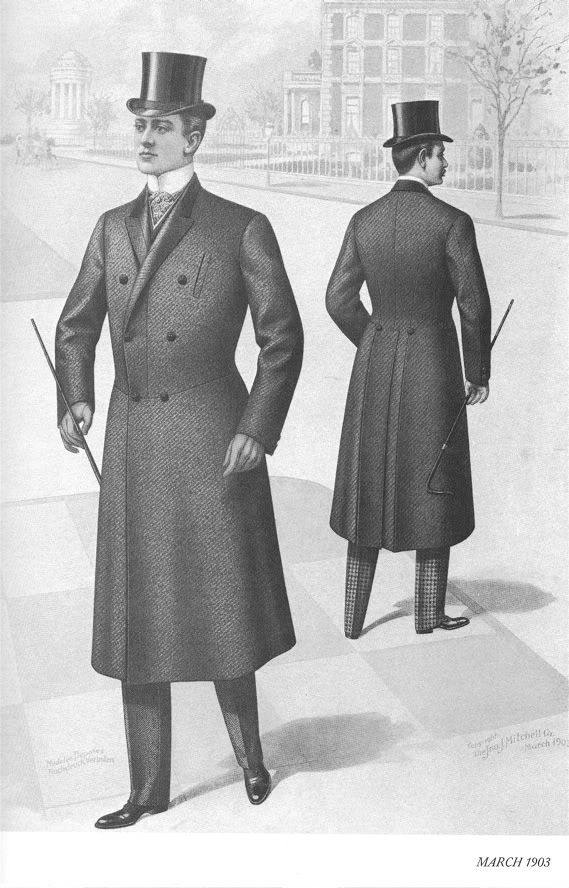

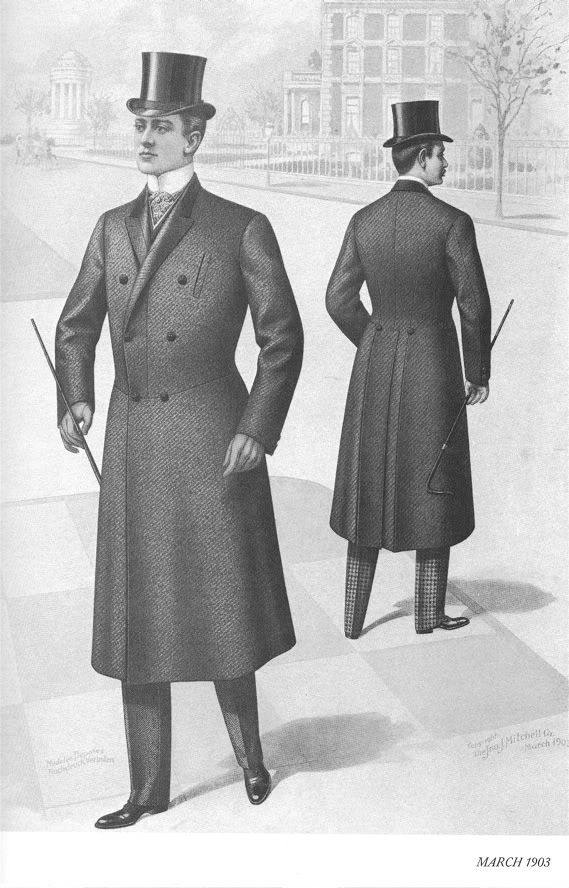

As you can see, the wearer has on a shirt, a waistcoat, a frock coat and over that he wears his final outer layer, the frock overcoat. The fact that it is indeed an overcoat is further highlighted by the fact that the garment has a velvet collar in a manner still commonly seen on Chesterfield coats today. Other characteristic features of the frock overcoat were that it often (but not always) had outer side pockets. In other respects, the basic cut and proportion of the frock overcoat are usually largely identical to that of the frock coat, although it is always cut to be a little longer than the frock coat underneath so as to fully cover the undercoat.

In this plate, it takes a little careful study of the coat to determine if it is a frock undercoat or a frock overcoat:

The things that give it away as a frock overcoat (or Albert top frock) are that it has a velvet collar and the sleeves lengths are slightly on the longer side. Although the chest welt could occasionally be found on frock coats, it is much more common on top frocks. It is also notable that the construction of the vent is identical to that of standard body coats worn as undercoats such as dress coats or morning coats.

In this illustration, the frock overcoat has side pockets – a feature never found on frock coats:

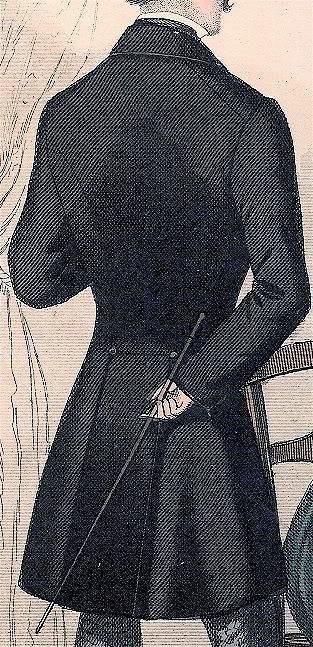

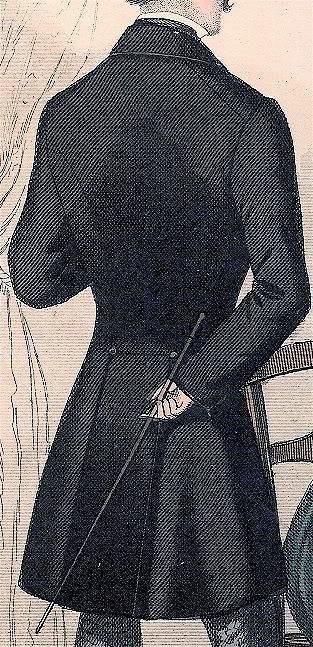

Sometimes, the frock overcoat had vents constructed differently to that of the undercoat:

The fashion plate also shows the above figure from the front - in the centre of the following three figures:

Seen from the front it is clear that the figure wears both a frock coat and frock overcoat. This demonstrates that the figure on the right shows off from behind, a method of the construction of the vents unique to the frock overcoat.

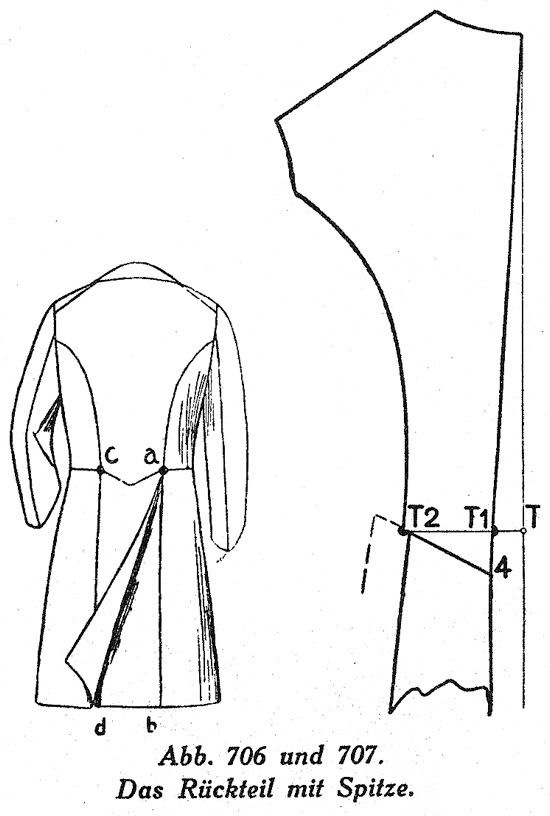

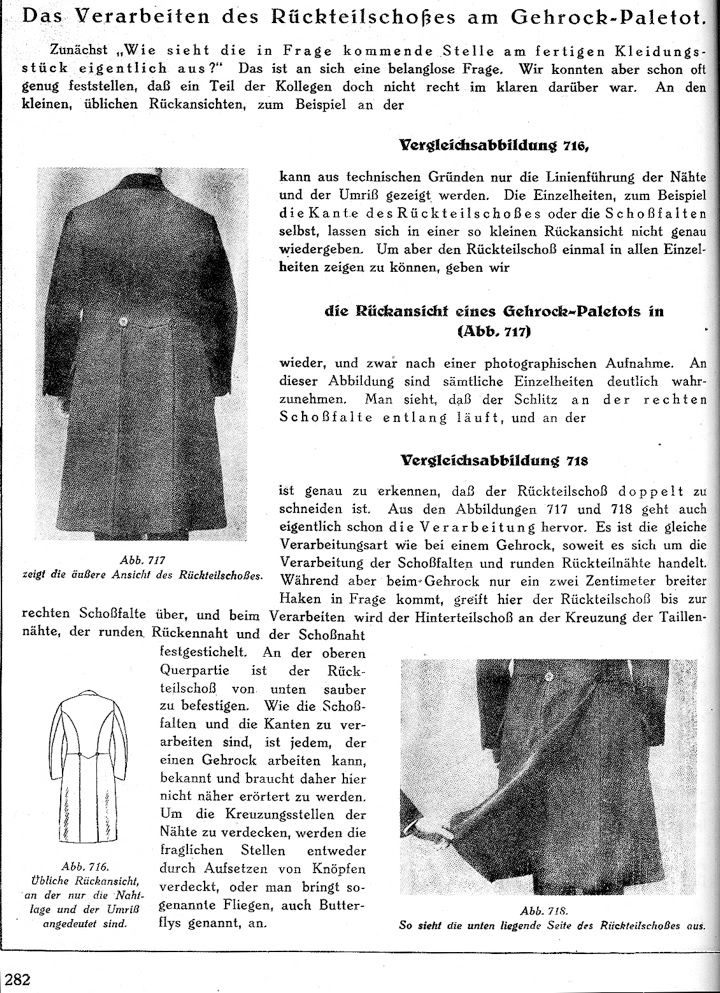

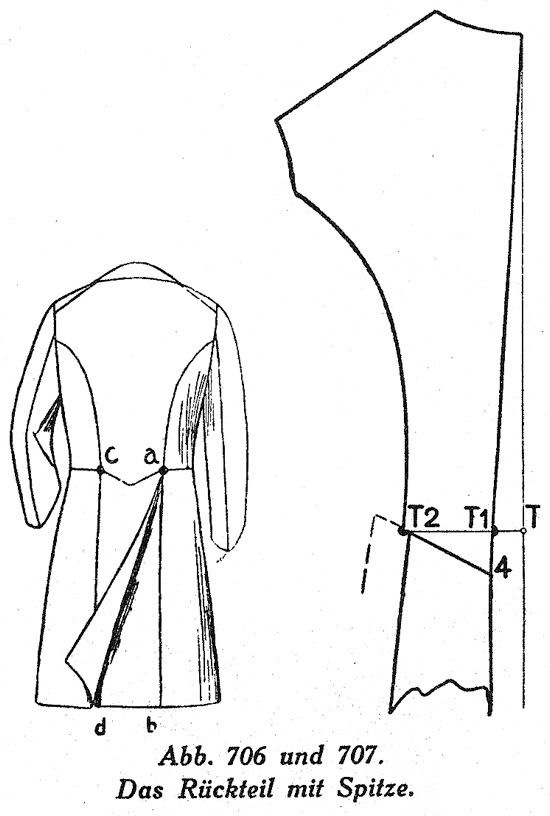

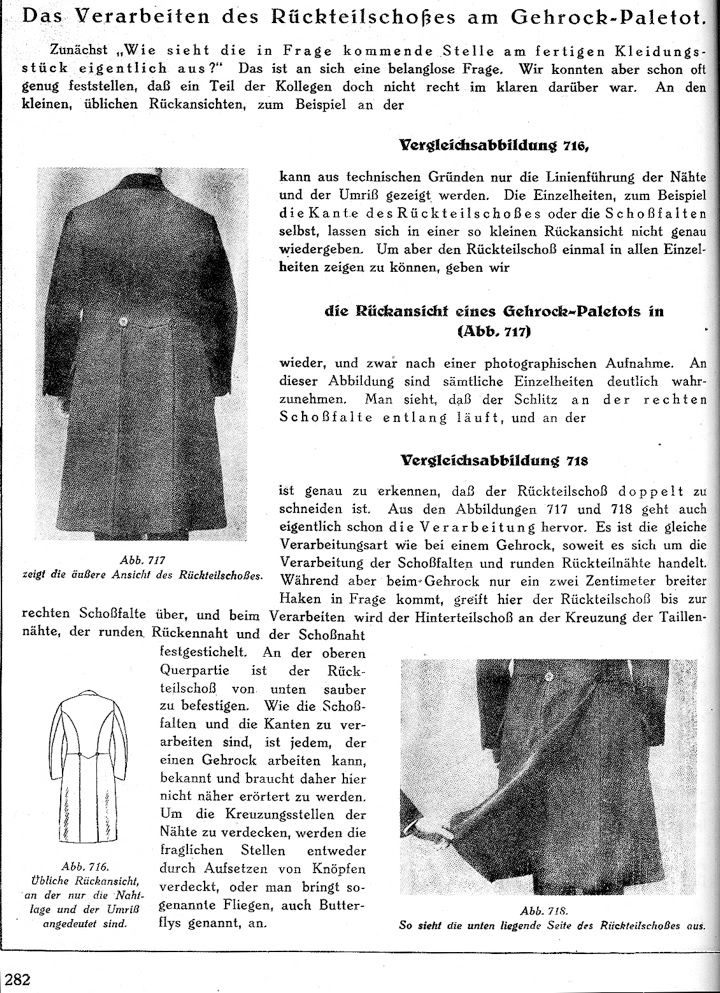

This old German text describes in detail the construction of what it calls a Gehrock-Paletot or frock overcoat:

Notice the way that the back panel is cut without a centre seam, and how the waist seam has been extended all the way around to meet at the centre back (between the buttons at the letters 'c' and 'a').

One AA/Esquire illustration that has engendered enormous confusion is this one. The wearers are in morning dress, and the overcoat of the figure on the right is described as a “paddock coat”.

Let us investigate in detail as to whether an error has been committed in calling this overcoat a “paddock coat”. The only detailed reference that explains what a paddock coat is found in Cunnington. The Cunningtons explain that some people in the late 19th century differentiated between the paletot and the paddock coat. The paletot properly had a side body, whereas the paddock coat lacks it. Cunnington states that the paddock coat is:

A long overcoat without a seam at the waist, made D-B or S-B and fly front

However, in common usage the term paletot was used for both. The important point is that the paddock coat (and paletot) was a sports overcoat that lacked a waist seam, and was never considered formal enough to wear with morning dress.

Let us look carefully at the illustration in concern:

It is quite clear that this is a body coat. The 6x3 construction is identical to a frock coat except for the outer pockets – just as would be expected from a frock overcoat. Also, a frock coat is worn with morning dress – and morning dress is depicted in the illustration. The velvet collar is another typical feature of a frock overcoat.

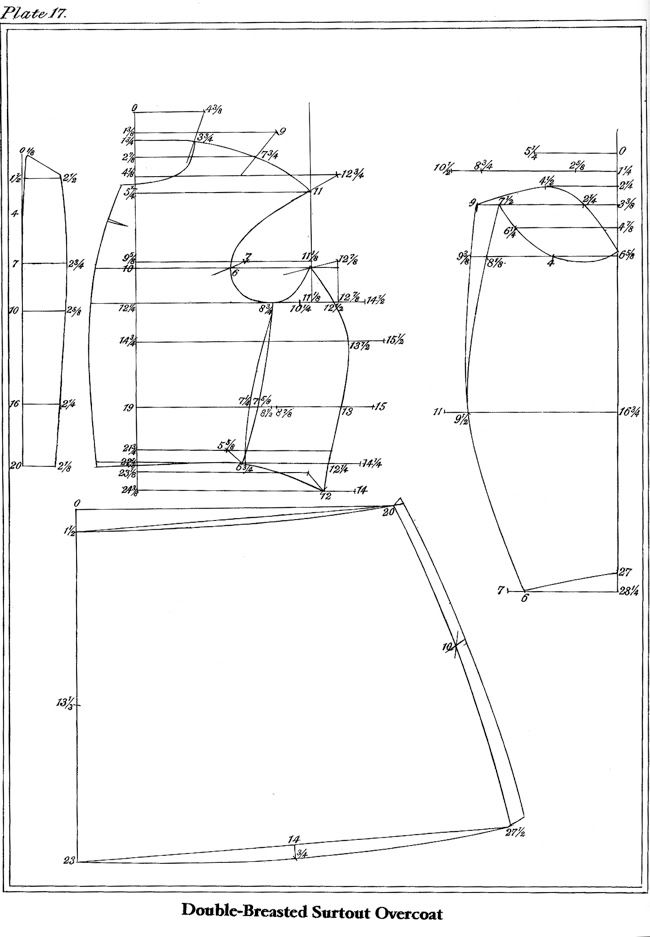

The next question is whether the fact that they American authors call it a "paddock coat" could reflect a difference in the usage between British and American English. The Cunningtons always use British English. However, examination of texts from Croonborg (New York-Chicago, 1907) reveals no mention of a paddock coat. However, he does call an overcoat with a body coat construction like a frock overcoat a “double-breasted surtout”.

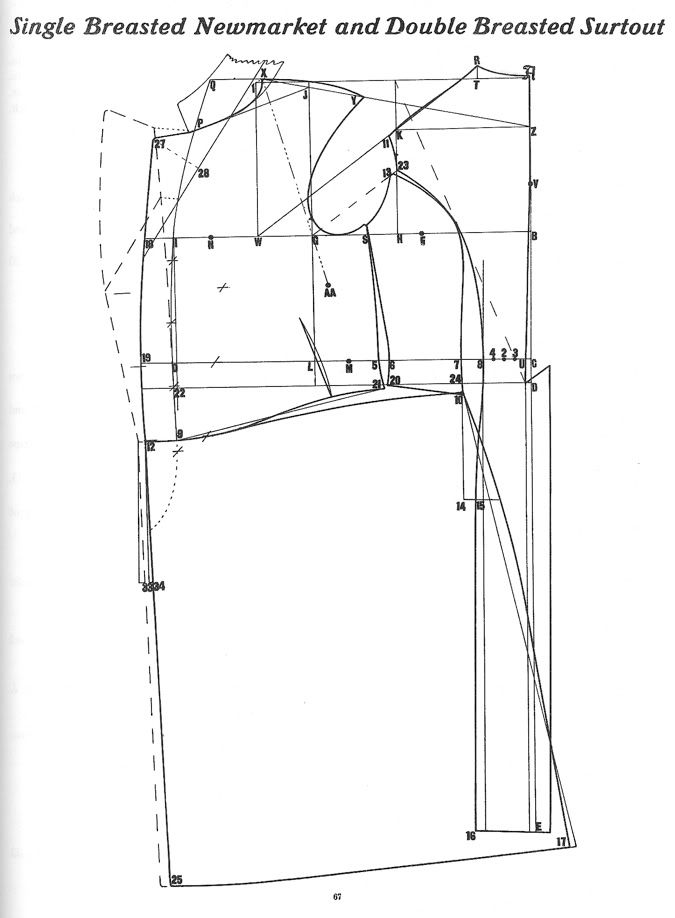

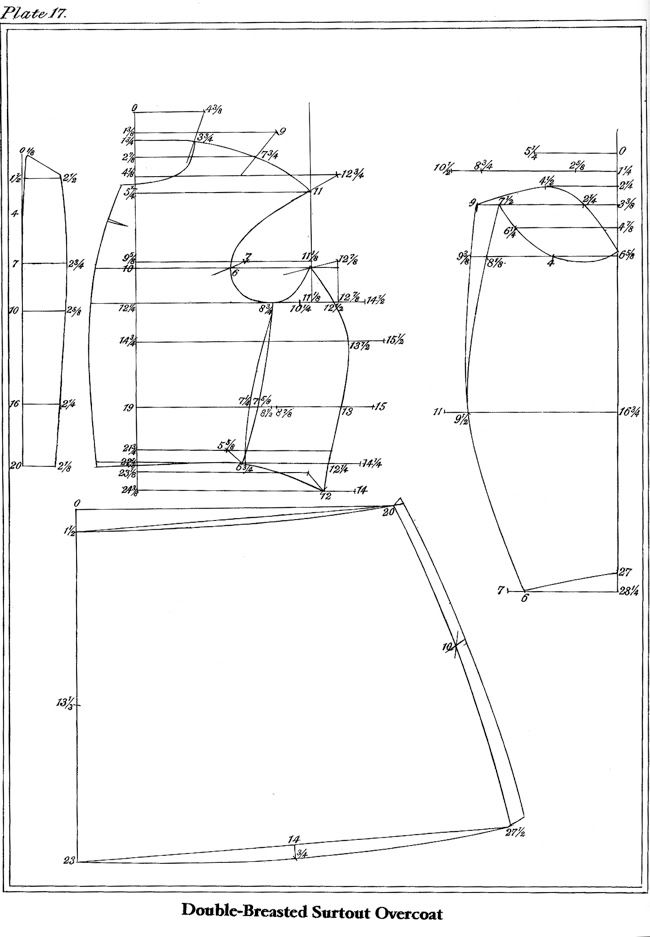

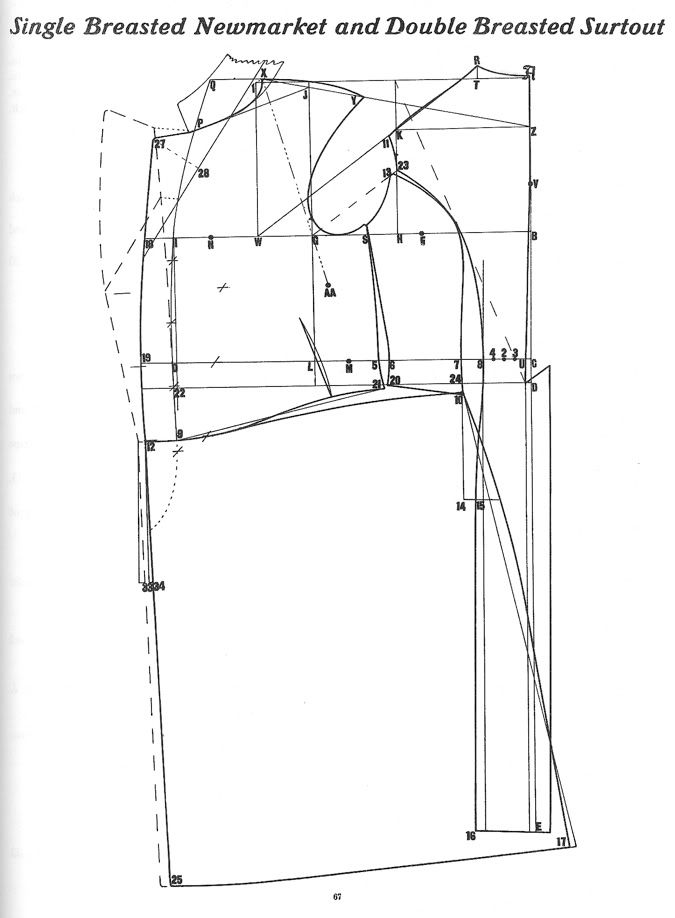

In British English, the word surtout became just another name for a frock coat after the 1850s. Salisbury (New York, 1865) likewise mentions no paddock coat and also calls such an overcoat version of the frock coat a "double-breasted surtout":

(Notice that Salisbury’s pattern has separately cut lapels, whereas Croonborg shows a one piece front, as was becoming fashionable around this time. Also, note the presence of the centre back seam and that the waist seam does not extend all the way to the centre back)

It seems that in American English the word surtout became restricted to describing a frock overcoat, whereas surtout became an alternative phrase for a frock undercoat in British English after the 1850's. The divergence in the usage of the term “surtout” argues for the origin of the later Victorian frock coat from a coat that was half overcoat and half undercoat. Nonetheless, it is clear that there was never a historical precedent in American English to call a double-breasted body overcoat a “paddock coat”.

It there was finally one last thing that must cast grave doubts on the term “paddock coat” in this usage, it must surely be the fact that a “paddock” would be a most peculiar place to wear such a formal full dress garment. The name automatically implies a country styled casual garment rather than a formal city garment.

The only logical conclusion is that the writers have made a rare mistake in this instance. The American writers in AA/Esquire should have called it a surtout. It is perhaps related to the fact that the garment had become increasingly rare at the time of printing, and the writers were unfamiliar with the correct terminology. At the time of writing, both paddock coat and frock overcoat were becoming extinct and the difference between them may have been lost on the authors.

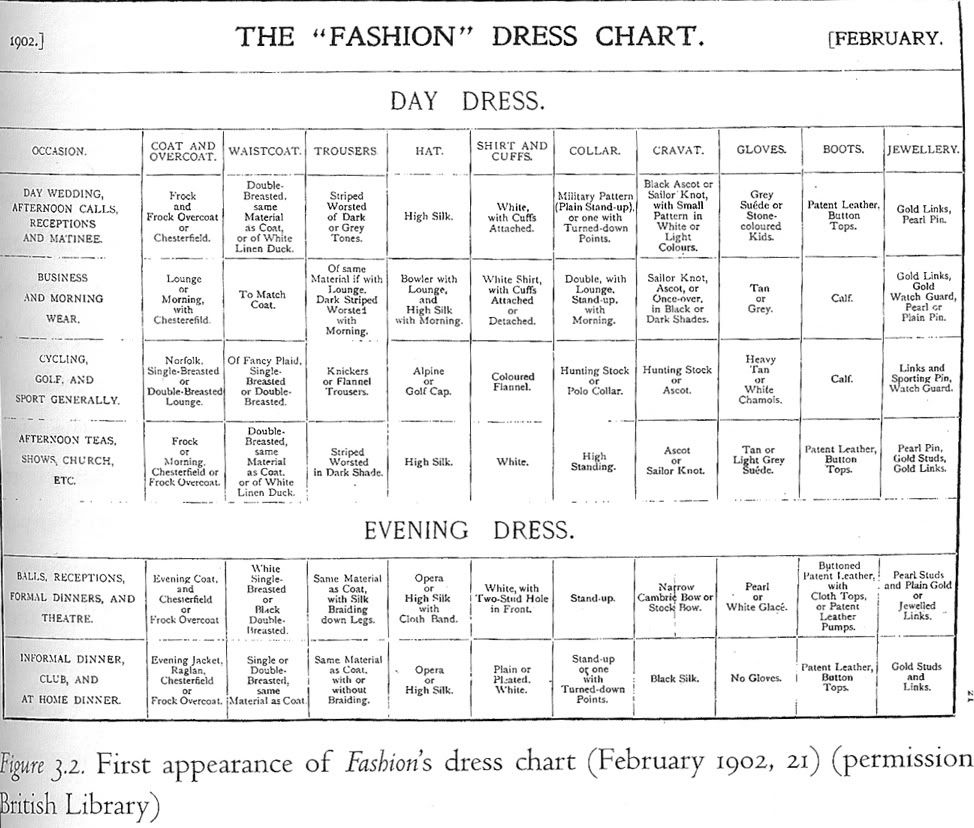

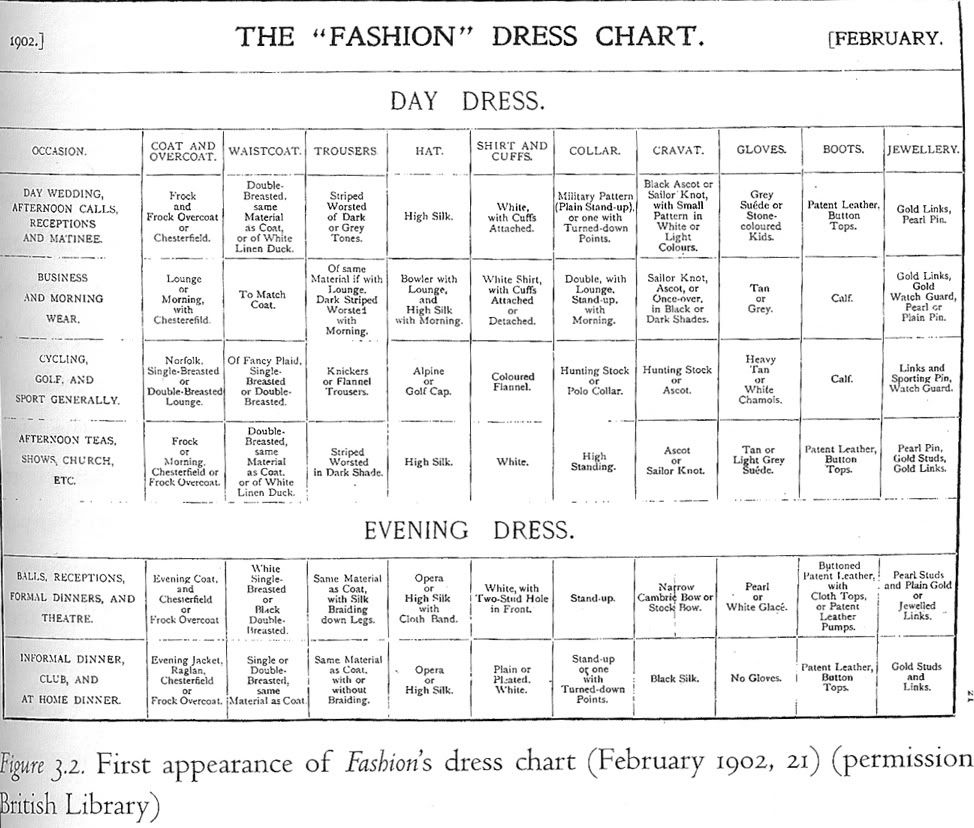

The next question is where such a garment could be worn. Originally, the frock overcoat was strictly worn only with daytime full dress and could not be worn in the evening, when an opera cape or Inverness cloak was required. However, this 1902 British dress chart makes it clear that it increasingly became acceptable to wear a frock overcoat with evening full dress:

Purist would have likely objected to this detail on this chart, insisting instead that a proper overcoat devoted to evening dress be worn such as an Inverness cloak or opera cape, which was loosely fitting to avoid disturbing the dress clothes underneath.

However, the frock overcoat remains - even to this day - a bit too formal a garment to wear with a lounge coat. In the daytime, the bare minimum level of formality would be that of a morning coat. The Chesterfield is much more suitable and a better match with the modern lounge coat. To reflect this American tailors used to call a Chesterfield an "over-sack" and a lounge coat a "sack coat" - terms which merely reflect their construction without a waist seam, so that they were not close fitting "body coats".

Those interesting in bespeaking a frock overcoat, should consider having a frock coat made up first. Once satisfied with your tailor’s pattern for the frock coat, a small measure can be added to the pattern of the overcoat. The above patterns from Salisbury and Devere may be used as the basis of your overcoat. Being a body coat it is cut to follow the contours of the body closely. There are two show buttons on the back, as is usual with body coats. The vents may be finished in the previously discussed manner with a back panel lacking a centre seam, and the waist seam extended to meet at the centre back, according to taste. Further details of this alternative method of construction can be found here:

The most typical colour would be black, but the suggestion to use dark navy is an interesting and highly tasteful one.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the frock coat established itself as the correct form of daywear full dress coat, displacing the dress coat to the status of evening wear.

It should also be made explicit that the word ‘coat’ does not traditionally denote outwear or an overcoat for outdoor wear. Tails coats such as the morning coat (day wear tail coat) and the dress coat (evening wear tail coat) are both coats, but are not outerwear. Coats can therefore be distinguished as either overcoats or ‘undercoats’ – although the latter archaic expression was used only in the early 19th century. The frock coat is an ‘undercoat’, and the top frock is an overcoat.

It is interesting that the frock coat may have evolved from a type of overcoat. Between 1820's to 1840's, a particular subtype of frock coat existed called the surtout that was half under-coat and half over-coat (Cunnington & Cunnington, The Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century). Here is an example from an original 1854 Parisian fashion plate I have in my possession:

Notice that the wearer is wearing only a waistcoat underneath the coat, thus making it an undercoat, which is nonetheless three quarter length in a manner more typical of overcoat. It has features that are half undercoat and half overcoat.

As the frock coat became established as the Prince Albert for wear with daytime full dress, an overcoat known as either a “top frock”, or the “frock overcoat” emerged, cut to be worn over the frock coat. Cutting manuals state that a little measure should be added to the proportions of the client’s frock coat to make this overcoat.

It cannot be emphasised strongly enough that the frock coat is not an overcoat or outerwear. When outerwear was worn, the frock overcoat served this role:

As you can see, the wearer has on a shirt, a waistcoat, a frock coat and over that he wears his final outer layer, the frock overcoat. The fact that it is indeed an overcoat is further highlighted by the fact that the garment has a velvet collar in a manner still commonly seen on Chesterfield coats today. Other characteristic features of the frock overcoat were that it often (but not always) had outer side pockets. In other respects, the basic cut and proportion of the frock overcoat are usually largely identical to that of the frock coat, although it is always cut to be a little longer than the frock coat underneath so as to fully cover the undercoat.

In this plate, it takes a little careful study of the coat to determine if it is a frock undercoat or a frock overcoat:

The things that give it away as a frock overcoat (or Albert top frock) are that it has a velvet collar and the sleeves lengths are slightly on the longer side. Although the chest welt could occasionally be found on frock coats, it is much more common on top frocks. It is also notable that the construction of the vent is identical to that of standard body coats worn as undercoats such as dress coats or morning coats.

In this illustration, the frock overcoat has side pockets – a feature never found on frock coats:

Sometimes, the frock overcoat had vents constructed differently to that of the undercoat:

The fashion plate also shows the above figure from the front - in the centre of the following three figures:

Seen from the front it is clear that the figure wears both a frock coat and frock overcoat. This demonstrates that the figure on the right shows off from behind, a method of the construction of the vents unique to the frock overcoat.

This old German text describes in detail the construction of what it calls a Gehrock-Paletot or frock overcoat:

Notice the way that the back panel is cut without a centre seam, and how the waist seam has been extended all the way around to meet at the centre back (between the buttons at the letters 'c' and 'a').

One AA/Esquire illustration that has engendered enormous confusion is this one. The wearers are in morning dress, and the overcoat of the figure on the right is described as a “paddock coat”.

Let us investigate in detail as to whether an error has been committed in calling this overcoat a “paddock coat”. The only detailed reference that explains what a paddock coat is found in Cunnington. The Cunningtons explain that some people in the late 19th century differentiated between the paletot and the paddock coat. The paletot properly had a side body, whereas the paddock coat lacks it. Cunnington states that the paddock coat is:

A long overcoat without a seam at the waist, made D-B or S-B and fly front

However, in common usage the term paletot was used for both. The important point is that the paddock coat (and paletot) was a sports overcoat that lacked a waist seam, and was never considered formal enough to wear with morning dress.

Let us look carefully at the illustration in concern:

It is quite clear that this is a body coat. The 6x3 construction is identical to a frock coat except for the outer pockets – just as would be expected from a frock overcoat. Also, a frock coat is worn with morning dress – and morning dress is depicted in the illustration. The velvet collar is another typical feature of a frock overcoat.

The next question is whether the fact that they American authors call it a "paddock coat" could reflect a difference in the usage between British and American English. The Cunningtons always use British English. However, examination of texts from Croonborg (New York-Chicago, 1907) reveals no mention of a paddock coat. However, he does call an overcoat with a body coat construction like a frock overcoat a “double-breasted surtout”.

In British English, the word surtout became just another name for a frock coat after the 1850s. Salisbury (New York, 1865) likewise mentions no paddock coat and also calls such an overcoat version of the frock coat a "double-breasted surtout":

(Notice that Salisbury’s pattern has separately cut lapels, whereas Croonborg shows a one piece front, as was becoming fashionable around this time. Also, note the presence of the centre back seam and that the waist seam does not extend all the way to the centre back)

It seems that in American English the word surtout became restricted to describing a frock overcoat, whereas surtout became an alternative phrase for a frock undercoat in British English after the 1850's. The divergence in the usage of the term “surtout” argues for the origin of the later Victorian frock coat from a coat that was half overcoat and half undercoat. Nonetheless, it is clear that there was never a historical precedent in American English to call a double-breasted body overcoat a “paddock coat”.

It there was finally one last thing that must cast grave doubts on the term “paddock coat” in this usage, it must surely be the fact that a “paddock” would be a most peculiar place to wear such a formal full dress garment. The name automatically implies a country styled casual garment rather than a formal city garment.

The only logical conclusion is that the writers have made a rare mistake in this instance. The American writers in AA/Esquire should have called it a surtout. It is perhaps related to the fact that the garment had become increasingly rare at the time of printing, and the writers were unfamiliar with the correct terminology. At the time of writing, both paddock coat and frock overcoat were becoming extinct and the difference between them may have been lost on the authors.

The next question is where such a garment could be worn. Originally, the frock overcoat was strictly worn only with daytime full dress and could not be worn in the evening, when an opera cape or Inverness cloak was required. However, this 1902 British dress chart makes it clear that it increasingly became acceptable to wear a frock overcoat with evening full dress:

Purist would have likely objected to this detail on this chart, insisting instead that a proper overcoat devoted to evening dress be worn such as an Inverness cloak or opera cape, which was loosely fitting to avoid disturbing the dress clothes underneath.

However, the frock overcoat remains - even to this day - a bit too formal a garment to wear with a lounge coat. In the daytime, the bare minimum level of formality would be that of a morning coat. The Chesterfield is much more suitable and a better match with the modern lounge coat. To reflect this American tailors used to call a Chesterfield an "over-sack" and a lounge coat a "sack coat" - terms which merely reflect their construction without a waist seam, so that they were not close fitting "body coats".

Those interesting in bespeaking a frock overcoat, should consider having a frock coat made up first. Once satisfied with your tailor’s pattern for the frock coat, a small measure can be added to the pattern of the overcoat. The above patterns from Salisbury and Devere may be used as the basis of your overcoat. Being a body coat it is cut to follow the contours of the body closely. There are two show buttons on the back, as is usual with body coats. The vents may be finished in the previously discussed manner with a back panel lacking a centre seam, and the waist seam extended to meet at the centre back, according to taste. Further details of this alternative method of construction can be found here:

The most typical colour would be black, but the suggestion to use dark navy is an interesting and highly tasteful one.